From “technocracy.news”

A thorough analysis of the ethics associated with brain-machine interfaces (BMI) that is lacking in the industry itself. In general, ethic studies typically do not exist in the Technocrat/Transhumanist industry because it hinders their advancement of technology. Technocrats invent because they can, not because there is a demonstrated need to do so.⁃ TN Editor

I’ve never wanted to be able to control any of my devices with my thoughts. I am perfectly happy to use a physical interface that I can turn off, let go of, or walk away from. What about you? Is your keyboard holding you back? Is your mouse slowing you down? Do you want to just think a post without having to thumb it in? Why is cyborgian tech being pushed so hard on us?

Did anyone ask for it? Does anyone need it?

In this essay, I will look at the ethicists who are raising concerns about Brain Machine Interface (BMI) technology, the projected utility of which would be the ability to swipe with your mind and to click with your brainwaves. Frankly, I don’t see a demand for that, not even for paralyzed people, since we have brain-surgery-free interfaces, such as those used by Stephen Hawking. Also, do we really want our impulsive rage tweets instantly sent?

No, no, no. That’s not where this tech is going. Nobody wants BMI to perform ordinary tasks in a new way, especially not if it means wearing some weird helmet all day or getting brain surgery. The carrot and stick here is the promise of enhanced mental abilities.

There seems to be a coordinated fearmongering campaign to convince us that, any moment now, transhumaned AI cyborg legions will out-perform us mentally. So everybody is going to have to get a BMI just to keep up. Unfortunately, when we do this, our brains will be readable to anyone with the right software, and we won’t be able to distinguish between our own decisions and those that are implanted in our heads via wireless devices.

Neuroethicists are suggesting that we have to act fast, maybe even rewrite our Constitutions!

I find that their new neurorights suggestions are designed, not to protect us so much as to limit the ways in which we may be violated for the greater good. Neuroethicists are wolves in sheep’s clothing. Let’s see if you agree with my assessment.

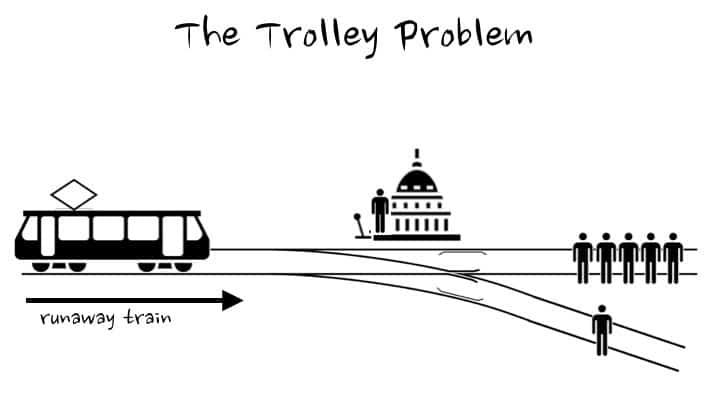

For the larger context, let’s first look at what’s known as the “Trolley Problem” in the field of ethics. Suppose a man is operating the switch station in a trainyard. If a runaway train trolley is about to plow into five workers on a track, is he morally obligated to pull the lever to reroute the trolley so that it only kills a single worker on another track?

You may notice that I have made a significant change to the standard image, this one lifted from Wikipedia, depicting this dilemma. My switchman is not acting under his own agency. He is a representative of government, acting according to some policy or standard procedure. That’s why he is pictured with a government building behind him. This change changes everything. According to protocol, he has to kill one guy to save five.

But when actions are automated, there is no agency, and therefore, what the man does cannot be described as choosing to act ethically. Old-time ethicists, for example Aquinas or Kant, argued that morality flows from the agent who freely decides the action, but today, the idea that an individual has the responsibility (not the freedom, not the right, but the responsibility) to choose between right or wrong has all but disappeared from the discussion of ethics.

Jose Munoz is with the Mind-Brain group in Spain, he is also at Harvard Medical and a few other really important places. Reviewing the work of a colleague, Nita Farahany, he sums up the approach of today’s neuroethicists to a T. He argues that we need to “establish guidelines for neural rights.” (Guidelines, that sounds gentle, but I wonder if they will have the kind of power of the CDC guidelines, which were implemented with all the force of law).

Munoz says there needs to be discussion between academics, governments, corporations and the public. (I wonder who is going to be doing all the talking in the discussion?) He says “citizens” must be guaranteed access to their data. (Okay, I have to jump through some hoops to find out what data has been collected on me without my knowledge or consent, and then what?)

I note the use of the word “citizens” instead of human beings or people.

He doesn’t want us to forget that, as citizens, we are subjects of a state. He also believes “a literacy around such data must be cultivated,” which is a weaselly way of saying people need to be told what to think about data collection. When were people asked to agree to data collection? The possibility of refusing to allow any data to be collected at all is not on this menu of ethical policies.

Nowadays, ethicists seem to just assume that ultimately the state needs to make those decisions about ethics—based on consensus, of course. So that’s okay because it’s a democratic loss of agency. Soon AI will be optimizing those decisions for us, we’re told. The individual human being has become a mere instrument through which someone else’s “ethical” choices are executed. This is not ethical. This is dangerous.

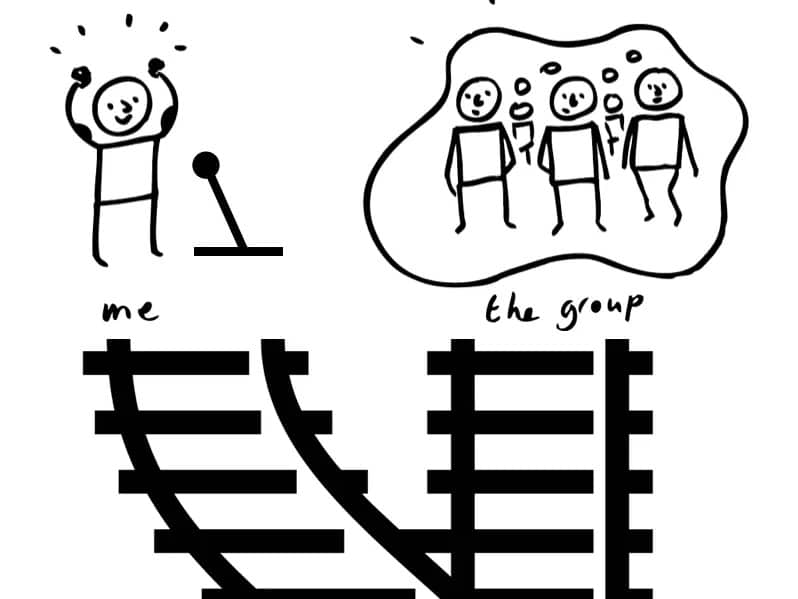

We can adapt the trolley problem to the question of whether or not the individual ought to make personal sacrifices for the good of society. The illustration below shows the kind of logic that says people ought to risk their lives in war for the good of their country, or take a vaccine that carries some risk because it is necessary for herd immunity.

In this essay, I will not argue that the individual has the right to be selfish and decide not to make personal sacrifices for the supposed good of others. That’s not why we must value individual responsibility over the collective good. We value individual responsibility because, if individuals are compelled, coerced or bribed to make sacrifices for the collective good, there is a grave danger that the entity that has the power to mandate policy could use that power to harm, unintentionally or intentionally.

At least when individual responsibility is granted, more brains are applied to problems and more opportunities will exist to find good solutions. Do we really want to wage war? Are vaccines actually safe and effective? Moreover, the mistakes an individual may make are usually confined to a small circle. The mistakes a policymaker makes affect the entire population.

After a three-year nightmare, in which Mistakes were Not Made—to reference Margaret Anna Alice’s poem by that title, accusing the “philanthropaths” and other leaders of intentional democide—we ought to be skeptical of any “ethicists” asking for more sacrifices from us to further policymakers’ notions of a greater good. As far as C0vlD goes, the consensus is developing that they got everything wrong: the lockdowns, masking and isolation, withholding early treatment and repurposed drugs, and promoting an experimental vaccine.

Lately, we are hearing quite a lot about the need to redefine human rights as the societal landscape adapts to new technologies that are changing what it means to be human. Claims are being made that a new “Transhumanism Ethics” is needed to save us from the dangers of hackers or governments and corporations who may want to employ AI to read our thoughts and control our minds.

Ienca and Andorno, authors of “Towards a New Human Rights in the Age of Neuroscience and Neurotechnology,” note how much information is collected on internet users now, and they assume that new technology will collect brain data too. These are the kinds of ethical considerations they ponder:

“For what purposes and under what conditions can brain information be collected and used? What components of brain information shall be legitimately disclosed and made accessible to others? Who shall be entitled to access those data (employers, insurance companies, the State)? What should be the limits to consent in this area?”

They do not even mention the more obvious argument that any online data collection could be considered a violation of privacy. Strangely, the first right they discuss in this paper is the right of individuals to decide to use emerging neurotechnologies. In their discussions, it is also assumed that the new technologies will do what they’re advertised to do. No discussions about the need for long-term studies or testing for possible technology blunders. We should recall that the Emergency Use Authorization for the C0vld vaccine was justified because it was said that people should have the right to use untested technology if they want.

In her discussion of neurorights being pushed in Chile, Whitney Webb notes that the poor and disenfranchised are being ushered to the front of the BMI trial volunteer line.

I happen to think that adults should be able to opt-in for new, possibly dangerous, therapies, get double D breast implants, commit suicide, do heroin, work as prostitutes or castrate themselves, if they freely choose to. But I don’t think it’s ethical to encourage or enable anyone to commit self-harm. An ethical society generally tries to help people see they may have other options. We don’t want to encourage people to take risks, certainly not unnecessary ones.

Ienca and Andorno also inform us that…

Most human rights, including privacy rights, are relative, in the sense that they can be limited in certain circumstances, provided that some restrictions are necessary and are a proportionate way of achieving a legitimate purpose. In specifically dealing with the right to privacy, the European Convention on Human Rights states that this right admits some restrictions ‘for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, or for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others’ (Art. 8, para 2).”

This sounds like Europeans do not have privacy rights; they have privileges that may be withdrawn any time the state deems it necessary.

It is well-known that godzillionaire Elon Musk, forsaking his pretensions to Libertarianism, wants government regulations on AI, even as he is hyping his invasive Neuralink AI tech, to be irreversibly implanted in human brains in order to read them. So far the test primates haven’t fared so well, and the Fall 2022 Show & Tell was underwhelming in the extreme. One problem, among the many they’ve had, was that the primate’s brainwave patterns for a particular letter that AI learned on one day, morphed into a different pattern five or six days later.

Way back when, Heraclitus already understood that we never step into the same river twice. All biological processes are dynamic and ever in flux, especially emergent brainwaves; they have to be because the world is too. Living beings must keep changing just to stay more or less the same. Computer algorithms, not even Deep Learning ones, are not as plastic as brainwaves.

Since the time of that cringy Show & Tell, Neuralink has been denied permission to prey upon human subjects, for the time being. But I doubt that this will prevent the bad money that has been thrown at this technology from attracting more good money. The investors have to make their pump money back before they dump. The FDA will come around.

I am not against technological transhumany progress that helps people overcome hardships. Bionic arms are awesome and even limb regeneration sounds like a great idea to pursue, carefully. But something is not right with this discussion of BMI tech and neurorights.

This year, Nita Farahany, Professor of Law and Philosophy, and self-described Nueroethicist at Duke University, has been promoting her new book, The Battle for Your Brain: Defending the Right to Think Freely in the Age of Neurotechnology, which defends nothing of the sort. In this book, she is not giving guidance to help people make the best ethical decisions for themselves and their families. She is trying to sell ethical norms to be imposed on us all.

In her book, and in a talk at a World Economic Forum meeting at Davos, Farahany opines with a forked tongue. For example, while initially defending the idea of mental privacy and “cognitive liberty” (Oh, brother, do they have to make up such awkward new terms?), she quickly concedes that it is not an absolute right—because, after all, one of the most basics things we do as humans is try to understand what our fellow humans are thinking. We must strike a balance, Farahany argues, between individual and societal interests. That means the policymakers get to decide which rights you need to give up.

For instance, she says it might be a good idea to make truckers wear EEG devices to monitor fatigue, for the collective good. If they fall asleep at the wheel, they could potentially kill five or six people. Can I suggest instead that truckers be paid reasonably well for the job they do, so that they don’t want to drive longer than eight hours per day? Alternatively, can we make our political representatives submit to constant surveillance of all their emails and phone calls and even in-person conversations? Because their decisions could potentially kill millions of people.

Farahany praises personal devices that monitor biological data for their potential to give workers quantitative data about their performance so that they can make “informed self-improvements.” The fact that FitBits are so popular, she claims, indicates that people are enthusiastic about being monitored and scored. But I am pretty sure Amazon warehouse workers are not clamoring for neurofeedback devices that will help them be more profitable for the stockholders.

Coerced monitoring and bogus quantitative assessment is unethical, I think.

Farahany concedes that such monitoring ought to be voluntary and believes that employees will want to accept these devices for self-improvement. Today, we have something similar with auto insurance; people get lower rates if they agree to be monitored while driving. But whenever there is a reward offered for sacrificing privacy, it is not ethical. It is coercive. The poor will more likely submit than the wealthy.

Is monitoring employee performance even helpful?

As Yagmur Denizhan argues in “Simulated Education and Illusive Technologies,” when people are put into situations where they are judged by points earned—not by more general and holistic qualitative evaluations—the crafty ones quickly focus on gaming the system so that they can earn more points, with less effort and lower quality work. But Farahany never questions the assumption that subjecting employees to negative and positive feedback will be good for productivity.