From “corbettreport.com”

What is BlackRock? Where did this financial behemoth come from? How did it gain such incredible power over the world’s wealth? And how is it seeking to leverage that power in shaping the course of human civilization? Find out in this in-depth Corbett Report documentary on How BlackRock Conquered the World.

Transcript

Hey! Let’s play a little game.

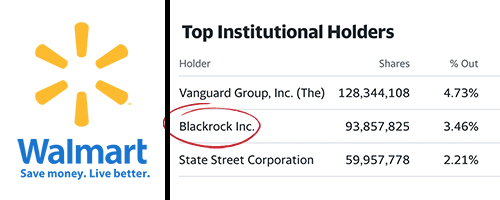

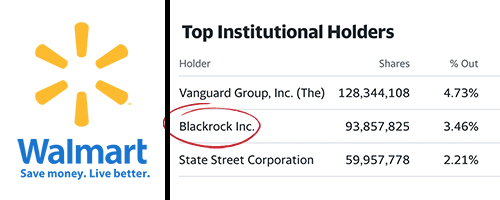

Let’s imagine you’re Joe Q. Normie and you need to run out for some groceries. You hop in the car and head to the store. What store do you go to? Why, Walmart, of course!

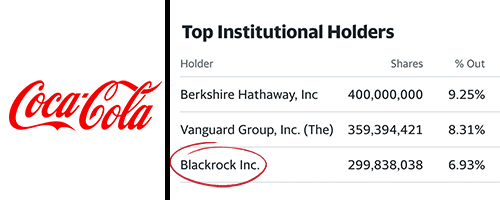

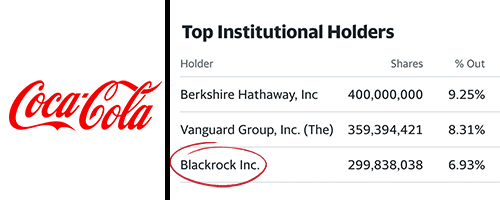

And, being an unwitting victim of the sugar conspiracy, what do you buy when you’re there? Coke, naturally!

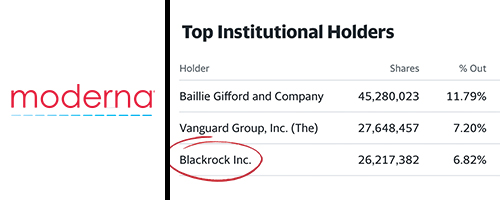

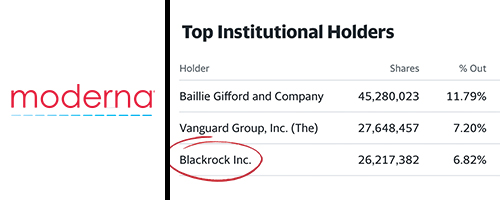

And you can get jabbed at Walmart these days, right? Well then, you might as well make sure you get your sixth Moderna booster while you’re there!

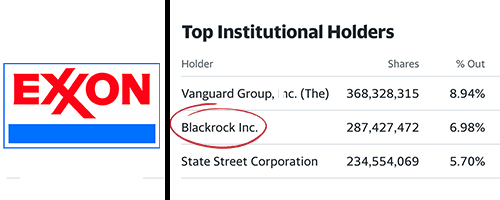

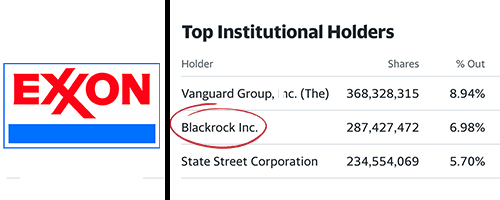

And don’t forget to fill up with gas on your way home!

Is this creeping you out? Then why don’t you shut yourself in your house and never go out shopping again? That’ll show ’em! After all, you can always order whatever you need from Amazon, can’t you?

Are you noticing a pattern here? Yes, in case you haven’t heard, BlackRock, Inc. is now officially everywhere. It owns everything.

Sadly for us, however, the creepy corporate claws of the BlackRock beast aren’t content simply to clutch onto a near plurality of the shares of every major corporation in the world. No, BlackRock is now digging its talons in even further and flexing its muscles, putting that inconceivable wealth and influence to use by completely reordering the economy, creating scamdemics and shaping the course of civilization in the process.

Let’s face it: if you’re not concerned about the power BlackRock wields over the world by this point, then you’re not paying attention.

But don’t worry if all of this is news to you. Most people have no idea where this investment giant came from, how it clawed its way to the top of the Wall Street dogpile, or what it has planned for your future.

Let’s fill in that gap in public understanding.

I’m James Corbett of The Corbett Report and today you’re going to learn the story of How BlackRock Conquered The World.

CHAPTER 1: A BRIEF HISTORY OF BLACKROCK

“Hold on a second,” I hear you interject. “I’ve got this! BlackRock was founded as a mergers and acquisitions firm in 1985 by a couple of ex-Lehmanites and has since gone on to become the world’s largest alternative investment firm, right?”

Wrong. That’s Blackstone Inc., currently headed by Stephen Schwarzman. But don’t feel bad if you confuse the two. The Blackstone/BlackRock confusion was done on purpose.

In fact, BlackRock began in 1988 as a business proposal by investment banker Larry Fink and a gaggle of business partners. The appropriately named Fink had managed to lose $100 million in a single quarter in 1986 as a manager at First Boston investment bank by betting the wrong way on interest rates. Humbled by this humiliating setback (or so the story goes), Fink turned lemons into lemonade by crafting a vision for an investment firm with an emphasis on risk management. Never again would Larry Fink be caught off guard by a market downturn!

Fink assembled some partners and brought his proposal to Blackstone co-founders Pete Peterson and Stephen Schwarzman, who liked the idea so much that they agreed to extend Fink a $5 million line of credit in exchange for a 50% share in the business. Originally named Blackstone Financial Management, Fink’s operation was turning a nice profit within months, had quadrupled the value of its assets in one year, and had grown the value of its portfolio under management to $17 billion by 1992.

Now firmly established as a viable business in its own right, Schwarzman and Fink began musing about spinning the firm off from Blackstone and taking it public. Schwarzman suggested giving the newly independent company a name with “black” in it as a nod to its Blackstone origins and Fink—taking roguish delight in the inevitable confusion and annoyance such a move would cause—proposed the name BlackRock.

STEPHEN SCHWARZMAN: So Larry and I were sitting down and he said, “what do you think about sort of having a family name? You know, with “black” in it. And I said that I think that’s a good idea. And I think he put on the table either BlackPebble or BlackRock. And so he said, “you know, if we do something like this, all of our people will kill us.”

The two evidently share the same sense of humour. “There is a little confusion [between the companies],” Schwarzman now concedes. “And every time that happens I get a real chuckle.”

But a shared taste for causing unnecessary confusion was not enough to keep the partners together. By 1994, the two had fallen out over compensation for new hires (or perhaps due to distress over Schwarzman’s ongoing divorce, depending who’s telling the story), and Schwarzman sold Blackstone’s holdings in BlackRock for a mere $240 million. (“That was certainly a heroic mistake,” Schwarzman admits.)

Having made the split with Blackstone and established BlackRock as its own entity, Fink was firmly on the path that would lead to his company becoming the globe-bestriding financial colossus that it is today.

In 1999, with its assets under management standing at $165 billion, BlackRock went public on the New York Stock Exchange at $14 per share. Expanding its services into analytics and risk management with its proprietary Aladdin enterprise investment system (more on which later), the firm acquired mutual fund company State Street Research & Management in 2004, merged with Merrill Lynch Investment Managers (MLIM) in 2006, and bought Seattle-based Quellos Group’s fund-of-hedge-funds business in 2007, bringing the total value of assets under BlackRock management to over $1 trillion.

But it was the Global Financial Crisis of 2007—2008 that catapulted BlackRock to its current position of financial dominance. Just ask Heike Buchter, the German correspondent who literally wrote the book on BlackRock. “Prior to the financial crisis I was not even familiar with the name. But in the years after the Lehman [Brothers] collapse [in 2008], BlackRock appeared everywhere. Everywhere!” Buchter told German news outlet DW in 2015.

Even before the Bear Sterns fiasco materialized into the Lehman Brothers collapse and the full-on financial bloodbath of September 2008, Wall Street was collectively turning to BlackRock for help. AIG, Lehman Brothers, Fannie Mae, and Freddie Mac had all hired the firm to comb through their spiraling mess of credit obligations in the months before the meltdown. BlackRock was perceived to be the only firm that could sort through the dizzying math behind the complicated debt swaps and exotic financial instruments underlying the tottering financial system and many Wall Street kingpins had Fink on speed dial as panic began to grip the markets.

“I think of it like Ghostbusters: When you have a problem, who you gonna call? BlackRock!” UBS managing director Terrence Keely told CNN at the time.

And why wouldn’t they trust Fink to pick through the mess of the subprime mortgage meltdown? After all, he was the one who helped launch the whole toxic subprime mortgage industry in the first place.

Oh, did I forget to mention that? Remember the whole “losing his job because he lost $100 million for First Boston in 1986” thing? That came just three years after Fink had made billions for the bank’s customers by constructing his first Collateralized Mortgage Obligation (CMO) and almost single-handedly creating the subprime mortgage market that would fail so spectacularly in 2008.

LARRY FINK: I started at First Boston in 1976. [. . .] I was the first Freddie Mac Bond Trader [. . .] and so the mortgage Market was just in its infancy. [. . .] And then in 1982 we had the ability to put a PC on our trading desk. Before that you had no ability to put a computer on that trading desk. And it was very clear to me that if we could have computing power on the trading desk, we were going to have the ability to dissect cash flows of mortgages.

That led in 1983 to the first carving up of a mortgage into different tranches. And so we created the first CMO.

SOURCE: Laurence Fink Talks investing and Blackrock Culture 2020

So, depending how you look at it, Fink was either the perfect guy to have in charge of sorting out the mess that his CMO monstrosity had created or the first fink who should have gone to jail for it. Guess which way the US government chose to see it?

Yes, you guessed right. They saw Fink as their saviour, of course.

Specifically, the US government turned to BlackRock for help, with beleaguered US Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner personally consulting Larry Fink no less than 49 times over the course of the 18-month crisis. Lest there be any doubt who was calling the shots in that relationship, when Geithner was on the ropes and his position as Secretary of the Treasury was in jeopardy at the end of Obama’s first term, Fink’s name was on the short list of those who were being considered to replace him.

The Federal Reserve, too, put its faith in BlackRock, turning to the company for assistance in administering the 2008 bailouts. Ultimately, BlackRock ended up playing a role in the $30 billion financing of the sale of Bear Stearns to J.P. Morgan, the $180 billion bailout of AIG, and the $45 billion rescue of Citigroup.

When the dust finally settled on Wall Street after the Lehman Brothers collapse, there was little doubt who was sitting on top of the dust pile: BlackRock. The only question was how they would parley their growing wealth and financial clout into real-world political power.

For Fink, the answer was obvious: move from the petty crime of high finance into the criminal big leagues of government. Accordingly, throughout the last decade, he has spent his time building up BlackRock’s political influence until it has become (as even Bloomberg admits) the de facto “fourth branch of government.”

When BlackRock executives managed to get their hands on a confidential Federal Reserve PowerPoint presentation threatening to subject BlackRock to the same regulatory regime as the big banks, the Wall Street behemoth spent millions successfully lobbying the government to drop the proposal.

But lobbying the government is a roundabout way to get what you want. As any good financial guru will tell you, it’s far more cost-efficient to make sure that no troublesome regulations are imposed in the first place. Perhaps that’s why Fink has been collecting powerful politicians for years now, scooping them up as consultants, advisors and board members so that he can ensure BlackRock has a key agent at the heart of any important political event.

As William Engdahl details in his own exposé of BlackRock:

BlackRock founder and CEO Larry Fink is clearly interested in buying influence globally. He made former German CDU MP Fridrich Merz head of BlackRock Germany when it looked as if he might succeed Chancellor Merkel, and former British Chancellor of Exchequer George Osborne as “political consultant.” Fink named former Hillary Clinton Chief of Staff Cheryl Mills to the BlackRock board when it seemed certain Hillary would soon be in the White House.

He has named former central bankers to his board and gone on to secure lucrative contracts with their former institutions. Stanley Fischer, former head of the Bank of Israel and also later Vice Chairman of the Federal Reserve, is now Senior Adviser at BlackRock. Philipp Hildebrand, former Swiss National Bank president, is vice chairman at BlackRock, where he oversees the BlackRock Investment Institute. Jean Boivin, the former deputy governor of the Bank of Canada, is the global head of research at BlackRock’s investment institute.

And it doesn’t end there. When it came time for Biden’s handlers to appoint the director of the National Economic Council—responsible for the coordination of policymaking on both domestic and international economic issues—naturally they turned to Brian Deese, the former global head of sustainable investing at BlackRock Inc.

And the rest, as they say, is history.

. . . or, more accurately, is the present. Because when we peel back the layers of propaganda from the past three years, we find that the remarkable events of the scamdemic have absolutely nothing whatsoever to do with a virus. We are instead witnessing a changeover in the monetary and economic system that was conceived, proposed and then implemented by (you guessed it!) BlackRock.

CHAPTER 2: GOING DIRECT

Historians of the future will no doubt note 2019 as the year that BlackRock began its takeover of the planet in earnest.

It was in January of that fateful year that Joe Biden crawled cap-in-hand to Larry Fink’s Wall Street office to seek the financial titan’s blessing for his presidential (s)election. (“I’m here to help,” Fink reportedly replied.)

Then, on August 22nd of 2019, Larry Fink joined such illustrious figures as Al “Climate Conman” Gore, Chrystia “Account Freezing” Freeland, Mark “GFANZ” Carney, and the man himself, Klaus “Bond Villain” Schwab, on the World Economic Forum’s Board of Trustees, an organization which, the WEF informs us, “serves as the guardian of the World Economic Forum’s mission and values.” (“But which values are those, precisely?” you might ask. “And what does Yo-Yo Ma have to do with it?”)

It was another event that took place on August 22, 2019, however, that captures our attention today. As it turns out, August 22nd was not only the date that Fink achieved his globalist knighthood on the WEF board, it was also the date that the financial coup d’état (later erroneously referred to as a “pandemic”) actually began.

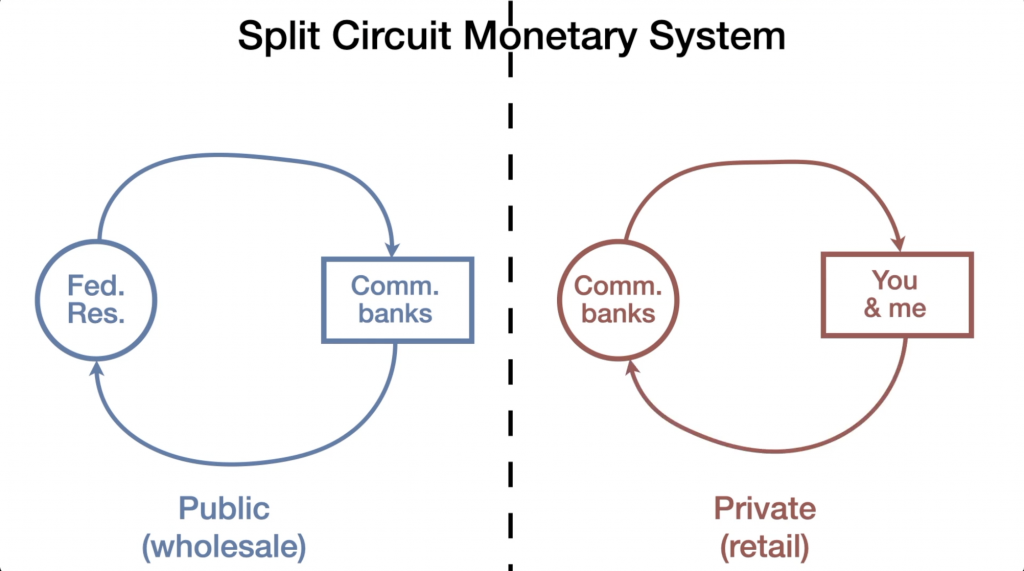

In order to understand what happened that day, however, we need to take a moment to understand the structure of the US monetary system. You see (GREATLY oversimplifying things for ease of understanding), there are actually two types of money in the banking system: there is “bank money”—the money that you and I use to transact in the real economy—and there is “reserve money”—the money that banks keep on deposit at the Federal Reserve. These two types of money circulate in two separate monetary circuits, sometimes referred to as the retail circuit (bank money) and the wholesale circuit (reserve money).

In order to get a handle on what this actually means, I highly suggest you check out John Titus’ indispensable videos on the subject, notably “Mommy, Where Does Money Come From?” and “Wherefore Art Thou Reserves?” and “Larry and Carstens’ Excellent Pandemic,” where he explains the split circuit monetary system.

JOHN TITUS: So here we have the split circuit monetary system. And on the left we have the public circuit, where I’m going to simplify the diagram. It’s the Federal Reserve issuing money to commercial banks and it is circling back to the Federal Reserve. The Federal Reserve might buy an asset from a commercial bank, which turns around and sells it back to the Fed. That’s a basic stripped-down circuit. In the retail circuit on the right—in red—the commercial banks are issuing money. Again, I’m going to simplify this. They issue money to you and me. They issue it in the form of loans. We pay the money back, and the cycle begins anew. And that’s really the system. I wanted to do this diagram, though, because you could see here, in the center of the diagram, the commercial banks occupy a special position in the two-tiered split circuit monetary system. They are both issuers and users of money—in the center here. So you could really draw a box around them. Now you and I, in the retail circuit, we keep our money on deposit at the commercial banks, which, in turn, keep their money on deposit at the Fed. So there you have two different systems of deposits.

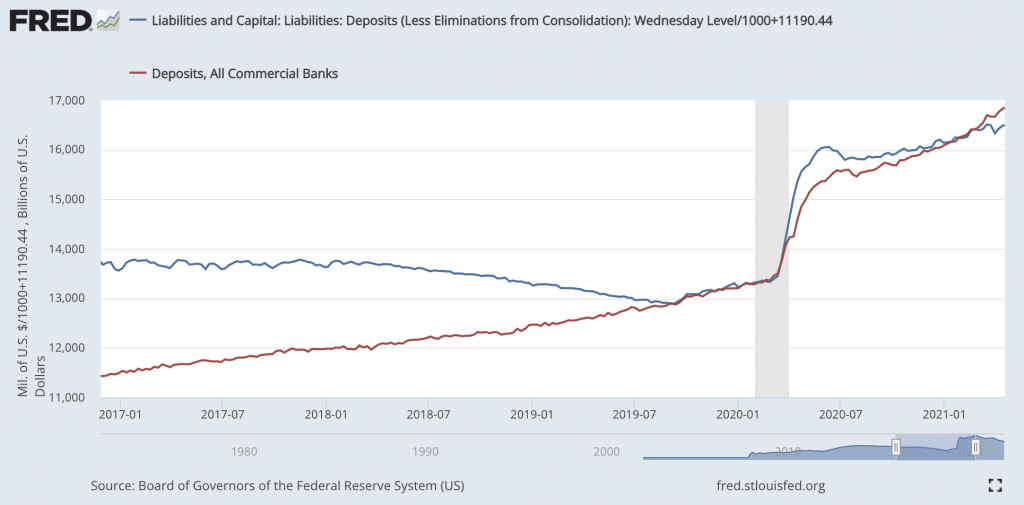

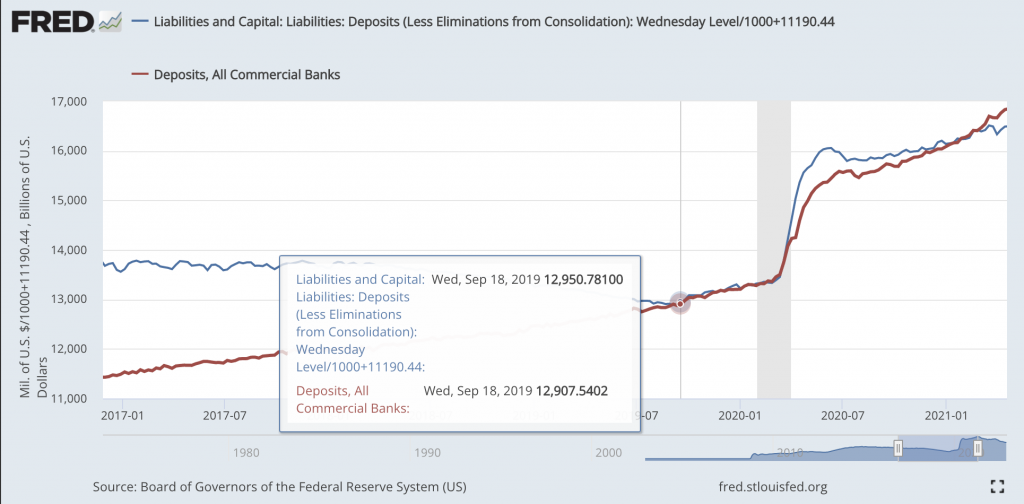

But the point of the two-circuit system is that, historically speaking, the Federal Reserve was never able to “print money” in the sense that people usually understand that term. It is able to create reserve money, which banks can keep on deposit with the Fed to meet their capital requirements. The more reserves they have parked at the Fed, the more bank money they are allowed to conjure into existence and lend out into the real economy. The gap between Fed-created reserve money and bank-created bank money acts as a type of circuit breaker, and this is why the flood of reserve money that the Fed created in the wake of the global financial crisis of 2008 did not result in a spike in commercial bank deposits.

But all that changed three years ago. As Titus observes, by the time of the scamdemic bailouts of 2020, the amount of bank money sitting in deposit in commercial banks in the US—a figure which had never shown any correlation with the total amount of reserves held on deposit at the Fed—suddenly spiked in lockstep with the Fed’s climbing balance sheet.

Clearly, something had happened between the 2008 bailout and the 2020 bailout. Whereas the tidal wave of reserve money unleashed to capitalize the banks in the earlier bailout hadn’t found its way into the “real” economy, the 2020 bailout money had.

So, what happened? BlackRock happened, that’s what.

Specifically, on August 15, 2019, BlackRock published a report under the typically eye-wateringly boring title, “Dealing with the next downturn: From unconventional monetary policy to unprecedented policy coordination.” Although the paper did not catch the attention of the general public, it did generate some press in the financial media, and, much more to the point, generated interest from the gaggle of central bankers who descended on Jackson Hole, Wyoming, for the annual Jackson Hole Economic Symposium taking place on August 22, 2019—the exact same day that Fink was being appointed to the WEF’s board.

The theme of the 2019 symposium—which brings together central bankers, policymakers, economists and academics to discuss economic issues and policy options—was “Challenges for Monetary Policy,” and BlackRock’s paper, published a week in advance of the event, was carefully crafted to set the parameters of that discussion.

It’s no surprise that the report caught the attention of the central bankers. After all, BlackRock’s proposal came with a pedigree. Of the four co-authors of the report, three of them were former central bankers themselves: Philipp Hildebrand, the former president of the Swiss National Bank; Stanley Fischer, the former Federal Reserve vice chairman and former governor of the Bank of Israel; and Jean Boivin, the former deputy governor of the Bank of Canada.

But beyond the paper’s authorship, it was what “Dealing with the next downturn” actually proposed that was to have such earthshaking effects on the global monetary order.

The report starts by noting the dilemma that the central banksters found themselves in by 2019. After years of quantitative easing (QE) and ZIRP (zero interest rate policy) and even the once-unthinkable NIRP (negative interest rate policy), the banksters were running out of room to operate. As BlackRock notes:

The current policy space for global central banks is limited and will not be enough to respond to a significant, let alone a dramatic, downturn. Conventional and unconventional monetary policy works primarily through the stimulative impact of lower short-term and long-term interest rates. This channel is almost tapped out: One-third of the developed market government bond and investment grade universe now has negative yields, and global bond yields are closing in on their potential floor. Further support cannot rely on interest rates falling.

So, what was BlackRock’s answer to this conundrum? Why, a great reset, of course!

No, not Klaus Schwab’s Great Reset. A different type of “great reset.” The “Going Direct” reset.

An unprecedented response is needed when monetary policy is exhausted and fiscal policy alone is not enough. That response will likely involve “going direct”: Going direct means the central bank finding ways to get central bank money directly in the hands of public and private sector spenders. Going direct, which can be organised in a variety of different ways, works by: 1) bypassing the interest rate channel when this traditional central bank toolkit is exhausted, and 2) enforcing policy coordination so that the fiscal expansion does not lead to an offsetting increase in interest rates.

The authors of BlackRock’s proposal go on to stress that they are not talking about simply dumping money into people’s bank accounts willy-nilly. As report co-author Philipp Hildebrand made sure to stress in his appearance on Bloomberg on the day of the paper’s release, this was not Bernanke’s “helicopter money” idea.

PHILIPP HILDEBRAND: Something that goes into the direction of essentially what we call going direct, which would be ways of putting money into pockets of consumers or corporates directly in order to spend. So, to go around the interest rate channel as opposed to traditional central banking, where you really only always work through the interest rate channel.

BLOOMBERG REPORTER: So, kind of like helicopter money? Do you have to be coordinated?

HILDEBRAND: Yeah, I think what it means helicopter money is a sort of catchphrase from the famous paper that Ben Bernanke gave in in the early 2000s. But the point is, yes, you have to go in a different way than working through the interest rate channel, because interest rates are already so low.

SOURCE: Risk of a Recession in 2020 Is More Elevated, Says BlackRock’s Hildebrand

Nor was it—as report co-author Jean Boivin was keen to stress in his January 2020 appearance on BlackRock’s own podcast discussing the idea—a version of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), with the government simply printing up bank money to spend directly into the economy.

No, this was to be a process where special purpose facilities—which they called “standing emergency fiscal facilities” (SEFFs)—would be created to inject bank money directly into the commercial accounts of various public or private sector entities. These SEFFs would be overseen by the central bankers themselves, thus crossing the streams of the two monetary circuits in a way that had never been done before.

Any additional measures to stimulate economic growth will have to go beyond the interest rate channel and “go direct” – when [sic] a central bank crediting private or public sector accounts directly with money. One way or another, this will mean subsidising spending – and such a measure would be fiscal rather than monetary by design. This can be done directly through fiscal policy or by expanding the monetary policy toolkit with an instrument that will be fiscal in nature, such as credit easing by way of buying equities. This implies that an effective stimulus would require coordination between monetary and fiscal policy – be it implicitly or explicitly. [Emphases added.]

Alright, let’s recap. On August 15, 2019, BlackRock came out with a proposal calling for central banks to adopt a completely unprecedented procedure for injecting money directly into the economy in the event of the next downturn. Then, on August 22, 2019, the central bankers of the world convened in Wyoming for their annual shindig to discuss these very ideas.

So? Did the central bankers listen to BlackRock? You bet they did!

Remember when we saw how commercial bank deposits began moving in sync with the Fed’s balance sheet for the first time ever? Well, let’s take another look at that, shall we?

It wasn’t the March 2020 bailouts where the correlation between the Fed balance sheet and commercial bank deposits—the tell-tale sign of a BlackRock-style “going direct” bailout—began. It was actually in September 2019—months before the scamdemic was a gleam in Bill Gates’ eye—when we started to see Federal Reserve monetary creation finding its way directly into the retail monetary circuit.

In other words, it was less than one month after BlackRock proposed this revolutionary new type of fiscal intervention that the central banks began implementing that very idea. The Going Direct Reset—better understood as a financial coup d’état—had begun.

To be sure, this going direct intervention was later offset by the Fed’s next scam for forcing more government debt on depositors, but that’s another story. The point is that the seal had been broken on the going direct bottle, and it wasn’t long before the central bankers had a perfect excuse for forcing that entire bottle down the public’s throat. What we were told was a “pandemic” was in fact, on the financial level, just an excuse for an absolutely unprecedented pumping of trillions of dollars from the Fed directly into the economy.

The story of precisely how the going direct reset was implemented during the 2020 bailouts is a fascinating one, and I would encourage you to dive down that rabbit hole, if you’re interested. But for today’s purposes, it’s sufficient to understand what the central bankers got out of the Going Direct Reset: the ability to take over fiscal policy and to begin engineering the economy of Main Street in a more . . . well, direct way.

But what did BlackRock get out of this, you ask? Well, when it came time to decide who to call in to manage the scamdemic bailout scam, guess who the Fed turned to? If you guessed BlackRock, then (sadly) you’re exactly right!

Yes, in March 2020 the Federal Reserve hired BlackRock to manage three separate bailout programs: its commercial mortgage-backed securities program, its purchases of newly issued corporate bonds and its purchases of existing investment-grade bonds and credit ETFs.

To be sure, this bailout bonanza wasn’t just another excuse for BlackRock to gain access to the government purse and distribute funds to businesses in its own portfolio, though it certainly was that.

And it wasn’t just another emergency where the chairman of the Federal Reserve had to put Larry Fink on speed dial—not simply to shower BlackRock with no-bid contracts but to manage his own portfolio—although it certainly was that, too.

It was also a convenient excuse for BlackRock to bail out one of its own most valuable assets: iShares, the collection of exchange traded funds (ETFs) that it acquired from Barclays for $13.5 billion in 2009 and that had ballooned to a $1.9 trillion juggernaut by 2020.

As Pam and Russ Martens—who have been on the BlackRock beat at their Wall Street On Parade blog for years now—detailed in their article on the subject, “BlackRock Is Bailing Out Its ETFs with Fed Money and Taxpayers Eating Losses“:

BlackRock is being allowed by the Fed to buy its own corporate bond ETFs as part of the Fed program to prop up the corporate bond market. According to a report in Institutional Investor on Monday, BlackRock, on behalf of the Fed, “bought $1.58 billion in investment-grade and high-yield ETFs from May 12 to May 19, with BlackRock’s iShares funds representing 48 percent of the $1.307 billion market value at the end of that period, ETFGI said in a May 30 report.”

No bid contracts and buying up your own products? What could possibly be wrong with that?

The numbers speak for themselves. After BlackRock was allowed to bail out its own ETF funds with the Fed’s newly minted going direct funny money, iShares surged yet again, surpassing $3 trillion in assets under management last year.

But it wasn’t just the Fed that was rolling out the red carpet for BlackRock to implement the very bailout plan that BlackRock created. Banksters from around the world were positively falling over themselves to get BlackRock to manage their market interventions.

In April 2020, the Bank of Canada announced that it was hiring (who else?) BlackRock’s Financial Markets Advisory (FMA) to help manage its own $10 billion corporate bond buying program. Then in May 2020, the Swedish central bank, the Riksbank, also hired BlackRock as an external consultant to conduct “an analysis of the Swedish corporate bonds market and an assessment of possible design options for a potential corporate bonds asset purchase programme.”

As we saw earlier, the Global Financial Crisis had put BlackRock on the map, establishing the firm’s dominance on the world stage and catapulting Larry Fink to the status of Wall Street royalty. With the 2020 Going Direct Reset, however, BlackRock had truly conquered the world. It was now dictating central bank interventions and then acting in every conceivable role and in direct violation of conflict-of-interest rules, acting as consultant and advisor, as manager, as buyer, as seller and as investor with both the Fed and the very banks, corporations, pension funds and other entities it was bailing out.

Yes, with the advent of the scamdemic, BlackRock had cemented its position as The Company That Owns The World.

But yet again we are left with the same nagging questions: what is BlackRock seeking to do with this power? What is it capable of doing? And what are the aims of Fink and his fellow travelers?

Let’s find out.

CHAPTER 3: Aladdin’s Genie and the Future of the World

As you now know, BlackRock started out life as “Blackstone Financial Management” in the offices of The Blackstone Group in 1988. By 1992, it was already so successful that founder Larry Fink and Blackstone CEO Stephen Schwarzman spun the company off as its own entity, christening it BlackRock in a deliberate attempt to sow confusion.

But it was in 1993 (or so the story goes) that arguably the most important of BlackRock’s market-controlling tools was forged. It was that year that Jody Kochansky, a fixed-income portfolio manager hired the year before, began to tire of his daily 6:30 AM task of comparing his entire portfolio to yesterday’s numbers.

The task, done by hand from paper printouts, was long and arduous. Kochansky had a better idea: “We said, let’s take this data, and rather than print it out, let’s sort it into a database, and have the computer compare the report today versus the report yesterday, across every position.”

It may seem obvious to us today, but in 1993 the idea of automating a task like this was a radical one. Nonetheless, it paid off. After seeing the utility of having an automated, daily, computer-generated report calculating the risk on every asset in a portfolio, Kochansky and his team hunkered down for a 72-hour code-writing exercise that resulted in Aladdin (short for “asset, liability, and debt and derivative investment network”), a proprietary investment analysis technology touted as “the operating system for BlackRock.”

Sold as a “central processing system for investment management,” the software is now the core of BlackRock Solutions, a BlackRock subsidiary that licenses Aladdin to corporate clients and institutional investors. Aladdin combines portfolio management and trading, compliance, operations and risk oversight in a single platform and is now used by over 200 institutions, including fund manager rivals Vanguard and State Street; half of the top ten insurers in the world; Big Tech giants like Microsoft, Apple and Alphabet; and numerous pension funds, including the world’s largest, the $1.5 trillion Japanese Government Pension Insurance Fund.

The numbers themselves tell the story of Aladdin.

It is used by 13,000 BlackRock employees and thousands of BlackRock customers.

It occupies three datacentres in the US, with BlackRock planning to open two more in Europe.

It runs thousands of Monte Carlo simulations—computational algorithms that model the probability of various outcomes in chaotic systems—every day on each one of the tens of millions of securities under its purview.

And, by February 2017, Aladdin was managing risk for $20 trillion worth of assets. That’s when BlackRock stopped reporting this figure, since—as the company told The Financial Times—”total assets do not reflect how clients use the system.” An anonymous source in the company had a different take: “[T]he figure is no longer disclosed because of the negative attention the enormous sums attracted.”

In this case, the phrase “enormous sums” almost fails to do justice to the truly mind-boggling wealth under the watchful eye of this computer system. As The Financial Times went on to report, the combination of the scores of new clients using Aladdin in recent years and the growth in the stock and bond markets in that time has meant that the total value of assets under the system’s management is much larger than the $20 trillion reported in 2017: “Today, $21.6tn sits on the platform from just a third of its 240 clients, according to public documents verified with the companies and first-hand accounts.”

For context, that figure—representing the assets of just one-third of BlackRock’s clientele—itself accounts for 10% of the value of all the stocks and bonds in the world.

But if the idea of this amount of the world’s assets being under the management of a single company’s proprietary computer software concerns you, BlackRock has a message for you: Relax! The official line is that Aladdin only calculates risk, it doesn’t tell asset managers what to buy or sell. Thus, even if there were a stray line of code or a wonky algorithm somewhere deep inside Aladdin’s programming getting its investment analysis catastrophically wrong, the final decision on any given investment would still come down to human judgment.

. . . Needless to say, that’s a lie. In 2017, BlackRock unveiled a project to replace underperforming human stockpickers with computer algorithms. Dubbed “Monarch,” the scheme saw billions of dollars of assets snatched from human control and given to an obscure arm of the BlackRock empire called Systematic Active Equities (SAE). BlackRock acquired SAE in the same 2009 deal that saw it snag iShares from Barclays Global Investors (BGI).

As we’ve already seen, the BGI deal was unbelievably lucrative for BlackRock, with iShares being purchased for $13.5 billion in 2009 and rising to a $1.9 trillion valuation in 2020. Testifying to BlackRock’s commitment to the machine-over-man Monarch project, Mark Wiseman, global head of active equities at BlackRock, told The Financial Times in 2018, “I firmly believe that, if we look back in five to 10 years from now, the thing that we most benefited from in the BGI acquisition is actually SAE.”

Even The New York Times was reporting at the time of the launch of the Monarch operation that Larry Fink had “cast his lot with the machines” and that BlackRock had “laid out an ambitious plan to consolidate a large number of actively managed mutual funds with peers that rely more on algorithms and models to pick stocks.”

“The democratization of information has made it much harder for active management,” Fink told The NY Times. “We have to change the ecosystem — that means relying more on big data, artificial intelligence, factors and models within quant and traditional investment strategies.”

Lest there be any doubt about BlackRock’s commitment to this anti-human agenda, the company doubled down in 2018 with the creation of AI Labs, which is “composed of researchers, data scientists, and engineers” and works to “develop methods to solve their hardest technical problems and advance the fields of finance and AI.”

The actual models that SAE uses to pick stocks is hidden behind walls of corporate secrecy, but we do know some details. We know, for instance, that SAE collects over 1,000 market signals on each stock under evaluation, including everything from the obvious statistics you would expect in any quantitative analysis of the equities markets—trading price, volume, price-earnings ratio, etc.—to the more exotic forms of data harvesting that are possible when complex learning algorithms are connected to the mind-boggling amounts of data now available on seemingly everyone and everything.

A Harvard MBA student catalogued some of these novel approaches to stock valuation undertaken by the SAE algorithms in a 2018 post on the subject.

One of the ways BlackRock is including machine learning in its investment process is by ‘signal combination’, in which a model mines data attempting to learn the relationships between stock returns and various quantitative data. For example, it would analyze web traffic through corporate’s websites as an indicator of future growth of the company or would look at geolocation data from smartphones to predict which retailers are more popular. In doing so, researchers must recalibrate and refine the model, to make sure it was adding value and not just rediscovering well known market behaviors already know [sic] by ‘fundamental’ fund managers.

Another important machine learning application came when it was combined with natural language processing. In this model, the technology learns in an adaptive way what are the words that can predict future performance of stocks. This model was used on analysis of broker reports and corporate filings, and the technology discovered that CEO’s remarks tend to be generally more positive, so then it started giving more importance to the comments of the CFO, or the Q&A portion of conference calls.

So, let’s recap. We know that BlackRock now manages well in excess of $21 trillion of assets with its Aladdin software, making a significant portion of the world’s wealth dependent on the calculations of an opaque, proprietary BlackRock “operating system.” And we know that Fink has “cast his lot in with the machines” and is increasingly devoted to finding ways to leverage so-called artificial intelligence, learning algorithms, and other state-of-the-art technologies to further remove humans from the investment loop.

But here’s the real question: what is BlackRock actually doing with its all-seeing eye of Aladdin and its SAE robo-stockpickers and its AI Labs? Where are Fink and the gang actually trying to take us with the latest and greatest in cutting-edge fintech wizardry?

Luckily, we don’t exactly need to scry the tea leaves to find our answer to that question. Larry Fink has been kind enough to write it down for us in black and white.

You see, every year since 2012, Fink has taken it upon himself as de facto ruler of the world’s wealth to pen an annual “letter to CEOs” laying out the next steps in his scheme for world domination.

. . . Errr, I mean, he writes the letter “as a fiduciary for our clients who entrust us to manage their assets – to highlight the themes that I believe are vital to driving durable long-term returns and to helping them reach their goals.”

Sometimes referred to as a “call to action” to corporate leaders, these letters from the man stewarding over a significant chunk of the world’s investable assets actually do change corporate behaviour. That this is so should be self-evident to anyone with two brain cells to rub together, which is precisely why it took a team of researchers months of painstaking study to publish a peer-reviewed paper concluding this blindingly obvious fact: “portfolio firms are responsive to BlackRock’s public engagement efforts.”

So, what is Larry Fink’s latest hobby horse, you ask? Why, the ESG scam, of course!

That’s right, Fink used his 2022 letter to harangue his captive audience of corporate chieftains about “The Power of Capitalism,” by which he means the power of capitalism to more perfectly control human behaviour in the name of “sustainability.”

Specifically:

It’s been two years since I wrote that climate risk is investment risk. And in that short period, we have seen a tectonic shift of capital. Sustainable investments have now reached $4 trillion. Actions and ambitions towards decarbonization have also increased. This is just the beginning – the tectonic shift towards sustainable investing is still accelerating. Whether it is capital being deployed into new ventures focused on energy innovation, or capital transferring from traditional indexes into more customized portfolios and products, we will see more money in motion.

Every company and every industry will be transformed by the transition to a net zero world. The question is, will you lead, or will you be led?

Oooh, oooh, I want to lead, Larry! Pick me, pick me! . . . but please, tell me how I can lead my company into this Brave New Net Zero World Order.

Stakeholder capitalism is all about delivering long-term, durable returns for shareholders. And transparency around your company’s planning for a net zero world is an important element of that. But it’s just one of many disclosures we and other investors ask companies to make. As stewards of our clients’ capital, we ask businesses to demonstrate how they’re going to deliver on their responsibility to shareholders, including through sound environmental, social, and governance practices and policies.

Yes, to the surprise of absolutely no one, Larry Fink has signed BlackRock on to the multi-trillion-dollar scam that is “environmental, social, and governance practices and policies,” better known as ESG. For those who don’t know about ESG yet, they might want to get up to speed on the topic with my presentation earlier this year on “ESG and the Big Oil Conspiracy.” Or they can read the summary of the ESG scam by Iain Davis in his article on the globalization of the commons (aka the financialization of nature through so-called “natural asset corporations”):

This will be achieved using Stakeholder Capitalism Metrics. Assets will be rated using environmental, social and governance (ESG) benchmarks for sustainable business performance. Any business requiring market finance, perhaps through issuing climate bonds, or maybe green bonds for European ventures, will need those bonds to have a healthy ESG rating.

A low ESG rating will deter investors, preventing a project or business venture from getting off the ground. A high ESG rating will see investors rush to put their money in projects that are backed by international agreements. In combination, financial initiatives like NACs and ESGs are converting SDGs into market regulations.

In other words, ESG is a set of phoney-baloney metrics that are being cooked up by globalist think tanks and would-be ruling councils (like the World Economic Forum) to serve as a type of social credit system for corporations. If corporations fail to toe the line when it comes to globalist policies of the moment—whether that’s committing to industry-destroying net zero (or even Absolute Zero) commitments or de-banking thought criminals or anything else that may be on the globalist checklist—their ESG rating will take a hit.

“So what?” you may ask. “What does an ESG rating have to do with the price of tea in China, and why would any CEO care?”

The “so what” here is that—as Fink signals in his latest letter—BlackRock will be putting ESG reporting and compliance in its basket of considerations when choosing which stocks and bonds to invest in and which ones to pass over.

And Fink is not alone. There are now 291 signatories to the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative, an “international group of asset managers committed to supporting the goal of net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 or sooner.” They include BlackRock, Vanguard, State Street and a slew of other companies collectively managing $66 trillion of assets.

In plain English, BlackRock and its fellow globalist investment firms are leveraging their power as asset managers to begin shaping the corporate world in their image and bending corporations to their will.

And, in case you were wondering, yes, this is tied into the AI agenda as well.

In 2020, BlackRock announced the launch of a new module to its automated Aladdin system: Aladdin Climate.

Aladdin Climate is the first software application to offer investors measures of both the physical risk of climate change and the transition risk to a low-carbon economy on portfolios with climate-adjusted security valuations and risk metrics. Using Aladdin Climate, investors can now analyze climate risk and opportunities at the security level and measure the impact of policy changes, technology, and energy supply on specific investments.

To get a sense of what a world directed by digital overlords at the behest of this ESG agenda might look like, we simply need turn to the ongoing conflict in Ukraine. As Fink wrote in his letter to shareholders earlier this year:

Finally, a less discussed aspect of the war is its potential impact on accelerating digital currencies. The war will prompt countries to re-evaluate their currency dependencies. Even before the war, several governments were looking to play a more active role in digital currencies and define the regulatory frameworks under which they operate. The US central bank, for example, recently launched a study to examine the potential implications of a US digital dollar. A global digital payment system, thoughtfully designed, can enhance the settlement of international transactions while reducing the risk of money laundering and corruption. Digital currencies can also help bring down costs of cross-border payments, for example when expatriate workers send earnings back to their families. As we see increasing interest from our clients, BlackRock is studying digital currencies, stablecoins and the underlying technologies to understand how they can help us serve our clients.

The future of the world according to BlackRock is now coming fully into view. It is a world in which unaccountable computer learning algorithms automatically direct investments of the world’s largest institutions into the coffers of those who play ball with the demands of Fink and his fellow travellers. It is a world in which transactions will be increasingly digital, with every transaction being data mined for the financial benefit of the algorithmic overlords at BlackRock. And it is a world in which corporations that refuse to go along with the agenda will be ESG de-ranked into oblivion and individuals who present resistance will have their CBDC wallets shut off.

The transition of BlackRock from a mere investment firm into a financial, political and technological colossus that has the power to direct the course of human civilization is almost complete.

JAMES O’KEEFE: Meet Serge Varlay, a recruiter at BlackRock.

SERGE VARLAY: Let me tell you, it’s not who the president is. It’s who’s controlling the wallet of the president.

UNDERCOVER REPORTER: And who’s that?

VARLAY: The hedge funds, BlackRock, the banks. These guys run the world.

Campaign financing. Yup, you can buy your candidates. Obviously, we have this system in place. First, there’s the senators. These guys are f***ing cheap. You got 10 grand? You can buy a senator. “I could give you 500k right now, no questions asked, Are you gonna do what needs to be done?”

REPORTER: Does, like, everybody do that? Does BlackRock do that?

VARLAY: Everyone does that. It doesn’t matter who wins. They’re in my pocket at this point.

SOURCE: BlackRock Recruiter Who ‘Decides People’s Fate’ Says ‘War is Good for Business’ Undercover Footage

CONCLUSION

As bleak as the exploration of this world-conquering juggernaut is, there is a ray of hope on the horizon: the public is at least finally becoming aware of the existence of BlackRock and its relative importance on the global financial stage. This is reflected in an increasing number of protests targeting BlackRock and its activities. For example:

NOW – BlackRock HQ in NYC stormed with pitchforks

Climate Activists March to BlackRock HQ for Occupy Park Ave Protests – NYC

Keen-eyed observers may note, however, that these protests are not against the BlackRock agenda I have laid out in this series. On the contrary. They are for that agenda. These protesters’ main gripe seems to be that Fink and BlackRock are engaged in greenwashing and that the mega-corporation is actually more interested in its bottom line than in saving Mother Earth.

Well, duh. Even BlackRock’s former Chief Investment Officer for Sustainable Investing wrote, after leaving the firm, an extensive four-part whistleblowing exposé documenting how the “sustainable investing” push being touted by Fink is a scam from top to bottom.

My only gripe with this limited hangout critique of BlackRock is that it implies that Fink and his cohorts are merely interested in accumulating dollars. They’re not. They’re interested in turning their financial wealth into real-world power. Power they will wield in service of their own agenda and will cloak with a phoney green mantle because they believe—and not without reason—that that’s what the public wants.

Slightly closer to the point, you get nonprofit groups like Consumers’ Research “slamming” BlackRock for impoverishing the real economy for the benefit of itself and its clients. “You’d think a company that has made it their mission to enforce ESG (environmental, social and governance) standards on American businesses would apply those same standards to foreign investments, but BlackRock isn’t pushing its woke agenda on China or Russia,” Consumers’ Research Executive Director Will Hild explained earlier this year after the launch of an ad campaign targeting the investment giant.

But that critique, too, seems to miss the underlying point. Is Hild trying to say that if only Fink applied his economy-destroying standards equally across the board then he would be beyond reproach?

More hopefully, there are signs that the political class—always willing to jump out in front of a parade and pretend they’re leading it—are picking up on the growing public discontent with BlackRock and are beginning to cut ties with the firm.

In recent months, multiple US state governments have announced their intention to divest state funds from BlackRock, with 19 states’ attorneys general even signing a letter to Larry Fink in August calling him out on his agenda of social control:

BlackRock’s actions on a variety of governance objectives may violate multiple state laws. Mr. McCombe’s letter asserts compliance with our fiduciary laws because BlackRock has a private motivation that differs from its public commitments and statements. This is likely insufficient to satisfy state laws requiring a sole focus on financial return. Our states will not idly stand for our pensioners’ retirements to be sacrificed for BlackRock’s climate agenda. The time has come for BlackRock to come clean on whether it actually values our states’ most valuable stakeholders, our current and future retirees.

As part of this divestment push, the Louisiana state treasurer announced in October that the state was withdrawing $794 million in state funds from BlackRock, South Carolina’s state treasurer announced plans to divest $200 million from the company’s control by the end of the year, and Arkansas has already taken $125 million out of money market accounts under BlackRock’s management.

As I noted in my appearance on The Hrvoje Morić Show, regardless of the real motivations of these state governments, the fact that they feel compelled to take action against BlackRock is itself a hopeful sign. It means that the political class understands that an increasing portion of the public is aware of the BlackRock/ESG/corporate governance agenda and is opposed to it.

Once again, we arrive at the bottom line: the only thing that truly matters is public awareness of the issues involved in the rise of a financial (and political and technological) giant like BlackRock, and it is only general public opinion that can move the needle when it comes to removing the wealth (and thus the power) from a behemoth like the one that Fink has created.

But before we wrap up here, there’s one last point to be made.

You might remember that we opened this exploration by highlighting BlackRock’s position as one of the top institutional shareholders in Walmart:

And in Coca-Cola:

And in Moderna:

And in Exxon:

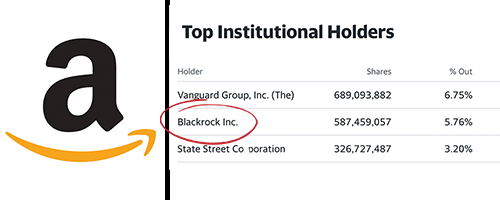

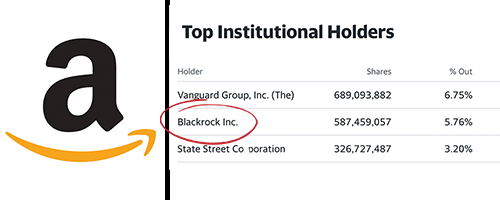

And in Amazon:

. . . and in seemingly every other company of significance on the global stage. Now, the fact checkers will tell you that this doesn’t actually matter because it’s the shareholders who actually own the stock, not BlackRock itself. But that raises a further question: who owns BlackRock?

Oh, of course.

Now, I realize this is a lot of information to take in at once. Go ahead and re-read this series once or twice. Follow some of the many links contained herein to better familiarize yourself with the material. Share these reports with others.

But if, after reading all of this you find yourself looking back over these “Top Institutional Holders” lists and saying: “Hey wait! Who’s The Vanguard Group?” . . .

. . . Well then, I’d say you’re starting to get it! Good job!

So who is the Vanguard Group? It’s an excellent question, and one that I’ll be answering in the next edition of The Corbett Report Subscriber newsletter! I hope you’re there for the answer!