From “brownstone.org”

he phenomenon of failing upward is only too familiar among the ranks of Australian politicians. People from other countries also come readily to mind as examples, including former US President Joe Biden, British Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer, and European Union President Ursula von der Leyen. Lately we’ve also witnessed this with an international organisation.

The World Health Assembly is the governing body of the World Health Organisation (WHO). It’s been meeting in Geneva this week (19–27 May) to adopt a new pandemic treaty that will reward the WHO for its gross mismanagement of the Covid pandemic by strengthening the framework for global health cooperation under WHO auspices. The accord’s focus is on building a global surveillance system to detect emerging pathogens and respond swiftly with coordinated measures, including the development and equitable distribution of medical countermeasures.

Yet, the premise of the accords is an inflated account of pandemic risk that is simply not supported by historical evidence. As a result, its effect will be to badly distort health priorities away from the real health needs and other social and economic goals of many countries. Only 11 countries abstained with 124 countries voting in support of adopting the new accords. The treaty will enter into force when 60 countries have ratified it

Whoever thought it was a good idea to give any bureaucracy and its head the power to declare a pandemic emergency that will expand its reach, authority, budget, and personnel and shift the balance of decision-making away from states to an unelected globalist bureaucrat? Or to adopt a One Health approach when the empirical reality is of sharply differentiated health vulnerabilities and disease burdens between regions? We need devolution, not more centralisation, with the principle of subsidiarity linking the distribution of authority and resources at the different levels.

Before empowering the WHO to cause even more harm, we should first investigate its Covid failings and decide if major reform can overcome the accumulated vested interests or if we need a new international health organisation. Any organisation that has been around for 80 years has either succeeded in its core mission, in which case it should be wound down out of existence. Or else it has failed, in which case it should be abolished and replaced by a new one that is more fit for purpose in today’s world.

WHO’s Failures to Speak Truth to Power and Profit

Speaking at a media briefing in Geneva on 3 March 2020, WHO Director-General (DG) Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said Covid’s case fatality rate (CFR) was 3.4 percent, against the seasonal flu’s CFR of below 1 percent. Addressing an internal meeting of the body negotiating a new pandemic agreement on 7 April 2025, he said: ‘Officially 7 million people were killed [by Covid], but we estimate the true toll to be 20 million.’

It’s hard to see why both statements, delivered five years apart as bookends to the Covid pandemic, do not constitute examples of misinformation. They are tantamount to catastrophisation and fear-mongering that spread alarm around the world at a rapid pace to begin with and then underpinned WHO efforts to commandeer even more powers and resources for future pandemic emergencies to be declared at the sole judgment of the WHO DG (Article 12 of the IHR). Yet in earlier drafts of the new pandemic accord, anyone who questioned the two sets of statistics would be guilty of spreading misinformation and could be sanctioned. For, like New Zealand’s Jacinda Ardern, the WHO must be revered as the single source of pandemic truth for the whole world.

On the total Covid mortality toll, forget the 20 million estimate. Almost all the alarmist calculations at the upper end of Covid-related deaths are derived from GIGO (garbage in, garbage out) computer modelling, not hard data. Even the seven million total does not discount the number of people in that age bracket (remember, the average age of Covid death is higher than life expectancy) who would have died of old age in the five-year period anyway. Nor those who died because early detection of treatable conditions were cancelled as part of lockdown measures; those who were admitted to hospitals with unrelated ailments but contracted Covid there; those who died with Covid after being injected with a Covid vaccine once, twice, or multiple times; or those who might have died from vaccine injuries.

As for the CFR, many experts immediately expressed scepticism that it was as high as 3.4 percent. Some cautioned against generalising from the distinctive Chinese experience. Mark Woolhouse, Professor of Infectious Disease Epidemiology at Edinburgh University, said as early as 4 March 2020 that the 3.4 percent CFR estimate could be up to ‘ten times too high,’ bringing it into line with some strains of influenza.

Firstly, the CFR is extremely challenging to estimate during an epidemic and in particular in its early days: it takes time for reliable data and trends to emerge, collate, and identify. The best estimates of CFR can only come when an epidemic is over. Deaths are confirmed as and when they occur but many early cases are missed or not reported. The true CFR and infection fatality rates (IFR) cannot be estimated until population seroprevalence (antibody) surveys are undertaken to establish the proportion of individuals who were infected, including those who did not manifest symptoms.

Yet, infamously, when Stanford’s Jay Bhattacharya [now the director of the National Institutes of Health (NIH)] and colleagues became the first to publish the results of a seroprevalence survey in Santa Clara County, California in early April 2020 which showed up a significantly higher infected population implying a correspondingly lower fatality rates, he was ferociously vilified and even investigated (but cleared) by his university. The results did not fit the catastrophist narrative. Yet another study by a different team in Orange County, California in February 2021 confirmed that the seroprevalence rate was seven times higher than the official county statistics. Other survey results from Germany and the Netherlands were also consistent with a higher infection rate.

Early data – from China, Italy, Spain, the Diamond Princess cruise ship – told us in February–March 2020 already that the most vulnerable were elderly people with existing serious health conditions. An early study from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention also confirmed the steep age gradient of Covid-related mortality: 0.2-0.4 percent for under-50s rising to 14.8 percent for those 80 and above. As early as 7 May 2020, a mainstream outlet like the BBC published a chart showing the risk of dying with Covid closely tracking the ‘normal’ distribution of age-stratified death rates.

In an October 2022 study that looked at 31 pre-vaccination national seroprevalence covering 29 countries to estimate the IFR stratified by age, John Ioannidis and his team found that the average IFR was 0.0003 percent at 0-19 years, 0.002 percent at 20-29 years, 0.011 percent at 30-39 years, and 0.035 percent at 40-49 years. The median for 0-59 year-olds was just 0.034 percent. These are well within and often lower than the seasonal flu range for the under-60s. The under-70s make up 94 percent of the world’s population or about 7.3 billion people. The age-stratified survival rate of healthy under-70s who were infected by Covid-19 before vaccines became available was a staggering 99.905 percent. For children and adolescents under 20, the survival rate is 99.9997 percent.

Experts from Oxford University’s Centre for Evidence Based Medicine used subsequent actual data to back-calculate a survival rate of 99.9992 percent for healthy under-20s in Britain. Official data from the UK Office for National Statistics for 1990–2020 show that the age-standardised mortality rate (deaths per 100,000 people) in England and Wales in 2020 was lower in 19 of the previous 30 years. Remember, this is before vaccines.

The doomsday model from Imperial College London’s Neil Ferguson on 16 March 2020 that precipitated lockdowns estimated the survival rate to be twenty times lower. There is a long track record of abysmally wrong catastrophist predictions on infectious diseases from this Pied Piper of Pandemic Porn: mad cow disease in 2002, avian flu in 2005, swine flu in 2009. Given his past record, why did anyone in authority give him a platform to propagate ‘The sky is falling’ yet again? He remains with the WHO Collaborating Centre for Infectious Disease Modelling at Imperial College London. This in itself is a sad and sorry indictment of the WHO.

The Disease Burden Spread by Income Level of Countries

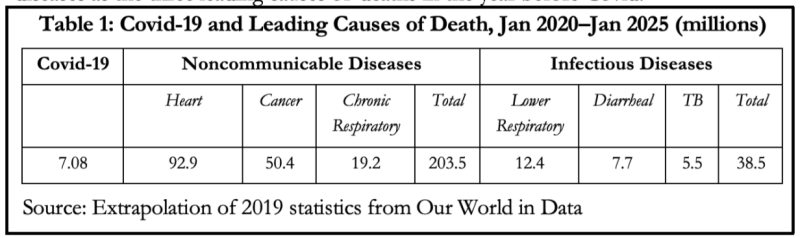

According to Our World in Data, in the five years from 4 January 2020 to 4 January 2025, 7.08 million people were officially confirmed as having died with Covid-19 around the world. According to the same source, 14 percent of the world’s 55 million deaths in 2019 were due to infectious diseases, including pneumonia and other lower respiratory diseases 4.4 percent, 2.7 percent diarrheal, and 2 percent tuberculosis. Another 74 percent were caused by noncommunicable diseases: 33 percent from heart diseases, 18 percent from cancers, and 7 percent from chronic respiratory diseases as the three leading causes of deaths in the year before Covid.

If we do a simple linear extrapolation, that means that in the same five-year period since January 2020, around 203.5 million people would have died from noncommunicable diseases and another 38.5 million from non-Covid infectious diseases (Table 1).

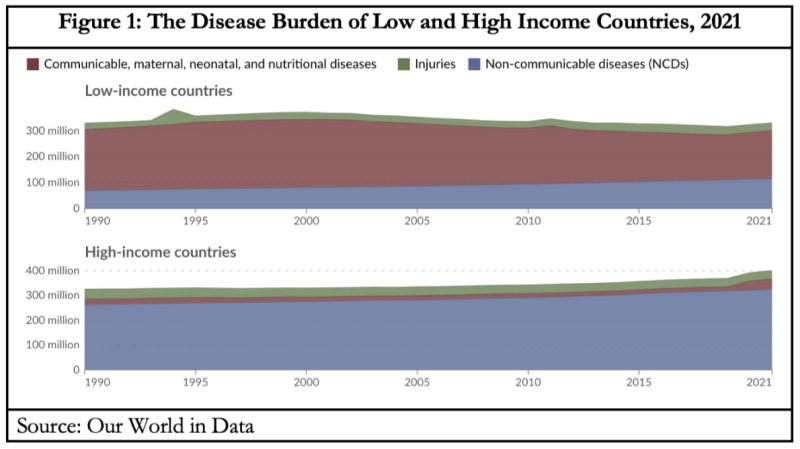

The sum of mortality and morbidity is called the ‘burden of disease.’ This is measured by a metric called ‘Disability Adjusted Life Years’ (DALYs). These are standardised units to measure years of lost health that help to compare the burden of different diseases in different countries, populations, and times. Conceptually, one DALY represents one lost year of healthy life – it is the equivalent of losing one year in good health because of either premature death or disease or disability.

Our World in Data breaks the disease burden down into three categories of disability or disease: noncommunicable diseases; communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional diseases; and injuries. Figure 1 illustrates the importance of disaggregating the disease burden, as measured by DALYs, between the low- and high-income countries instead of lumping them into one catch-all category that loses conceptual coherence. The total DALYs in the former in 2021 were 331.3 million and in the latter, 401.2 million.

In the low-income countries, the percentage share of DALYs due to communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional diseases was 55.8 percent, while that due to noncommunicable diseases was 34.7 percent. But in the high-income countries, they were 10.5 and 81.1 percent. That is why Covid-19 was a relatively far more serious threat to the rich countries compared to the poor countries. But even for them, this was true only during the brief period of the pandemic, which reduces to a mere blip in the long view.

The relative disease burden of pandemics is even less salient when we recall that in the period during which the WHO has been in existence, the only other pandemics to have occurred were the Asian and Hong Kong flu pandemics in 1957–58 and 1968–69, in each of which around two million people died (the WHO gives the death estimates as 1.1 and 1 million respectively – thanks David Bell); and the swine flu pandemic in 2009–10, in which between 0.1 and 1.9 million people died (the WHO estimates the range as 123,000-203,000). The Russian flu pandemic of 1977 was even milder. The historical timeline of pandemics shows how improvements in sanitation, hygiene, potable water, antibiotics, and other forms of expanding access to good healthcare have massively reduced the morbidity and mortality of pandemics since the Spanish flu (1918–20) in which 50-100 million people are estimated to have died.

Pandemics Require Policy Trade-Offs

In responding to an epidemic or pandemic, there is a trade-off between public health, economic stability, and individual well-being. It is the duty of health professionals to focus solely on the first. It is the responsibility of governments to strike the optimum balance and intuit the social fulcrum: the sweet spot at the intersection of dangerous complacency, alarmist panic, and reasonable precautions. The injunction to first do no harm implies that governments should be wary of prolonged economic lockdowns: the cure might indeed be worse than the disease. In earlier flu epidemics, the numbers infected and killed were sufficient to produce a severe impact on society. But governments didn’t shut down their country, destroy the economy nor jeopardise their way of life. People suffered but endured.

In the case of Covid-19, almost all the mistakes and damage can be traced back to two mutually contradictory assumptions, neither of which was ever revised back to the mean. First, assume the absolute worst about the pandemic on infectivity, speed of progression in the infected, rate of cross-infection, lethality, and lack of treatment options. Second, assume the very best about the effectiveness of all policy interventions, regardless of the existing science and lack of any real world data (some rules like universal masking and two-metre physical separation were based on rushed but flawed research and guesswork), the cries of caution from a wide range of well-credentialled and well-meaning specialists with no private agenda and financial conflicts of interest, and the need for careful analyses of the risk profiles of population cohorts for the virus and the harms-benefits equation of interventions. The two sets of extreme assumptions were then used to embark on radical new interventions that had never before been tried at global and universal scale.

WHO’s Sins of Commission and Omission

The WHO should have stepped in immediately as the international institutional firewall against this. It did not. The top leadership of the WHO joined national health-bureaucracy counterparts in the world’s most powerful and influential countries in the belief that they knew best and colluded in the brutal drowning of all dissenting voices. The consequences were catastrophic and have caused lasting damage to public health. Dr Jay Bhattacharya, the new NIH director, was interviewed by Politico recently. He identified both his own NIH and the WHO as among the leading examples of institutions of this dual pathology. They:

… convinced governments around the world that the only way to save lives was to follow the lockdown path and that they needed extraordinary, almost dictatorial powers, suppressing free speech, suppressing freedom of movement, suppressing the principle of informed consent in medical decision-making, controlling nearly every single aspect of society, designating who’s essential and who’s not essential, closing churches, closing businesses.

And they made this decision for the whole world…

The WHO failed the peoples of the world by becoming a cheerleader for panicked responses instead of holding the line on existing science, knowledge, and experience. This was summarised in its own report of 19 September 2019 that advised against lockdowns, other than for very short periods, border closures, masks in general community settings, etc. The WHO proved too credulous of early Chinese data on the risk of human-human transmission, no Wuhan lab origin, lethality, and effectiveness of tough containment measures. The first WHO panel to investigate the origins of Covid was riddled with conflicts of interest of key panel members and again gave China a free pass. A follow-up investigation was thwarted by active non-cooperation from China, for which it failed to be held to account.

Other WHO sins of commission included exaggerations of Covid lethality by presenting highly inflated case fatality rates; obfuscation on the age-stratified risk profile of severe illness and mortality from Covid; unscientific recommendations on mask mandates and later vaccine passports, or at least failure to combat them; and complicity in the human rights abuses committed in pursuit of the fool’s gold of Covid eradication. For example, the SARS-CoV-2 virus was never a good candidate for vaccination owing to its low virulence, high transmissibility, and rapid mutation characteristics. Nor did it take long for data to confirm the highly unfavourable risk-benefit equation of Covid-19 vaccines.

Sins of omission included downplaying the predictable and predicted short and long-term health, mental health, educational, economic, social, and human rights harms of the drastic interventions like school closures; the escalation of avoidable non-Covid deaths through disrupted food production and distribution, disrupted childhood immunisation programs in low income countries and deferred and cancelled early detection programs and treatment of cancers, etc in industrialised countries; the deaths of despair of elderly people cut off from the emotional support crutches of loved family; the inflationary spirals that are yet to subside from government support schemes to compensate for loss of incomes owing to economic shutdowns; and the substantial erosion of trust in public institutions in general and public health institutions in particular.

WHO advice on Covid management also seemed to prioritise the high disease burden of industrialised over developing countries and the interests of the major global pharmaceutical companies over patients, for example in the way that the promising potential of some repurposed drugs with well-established safety profiles were discounted and even mocked and ridiculed instead of being impartially investigated. Yet, there have been no admissions of culpability, no apologies for the extensive and lasting damage inflicted, and no accountability for those responsible for unleashing and cheerleading the public policy insanity.

Trump’s America Exits the WHO

Of course, WHO recommendations are not legally binding obligations on treaty signatories. The treaty explicitly states that nothing in it gives the WHO or the DG ‘any authority to direct, order, alter or otherwise prescribe’ any policy; or to mandate or…impose any requirements’ that states parties ‘take specific actions’ like travel bans, vaccination mandates, or lockdowns (Article 22.2). However, the very first function of the WHO is described in its constitution as ‘to act as the directing and coordinating authority on international health work’ (Article 2.a). The Pandemic Treaty’s preamble recognises that the WHO ‘is the directing and coordinating authority on international health work, including on pandemic prevention, preparedness and response.’

In combination with the amended International Health Regulations (IHR) that come into force this September and which must and will be read in parallel, the political reality is that member states will be enmeshed into the international pandemic management framework led by international technocrats who lack the legitimacy of democratically elected political leaders, are not in practice accountable, and who have been given this enhanced directive role without meaningful parliamentary scrutiny or public debate by citizens.

Nothing in the Covid experience inspires confidence about the willingness and capacity of political leaders to resist WHO recommendations in this global institutional milieu. Rather, a de facto realignment of chairs at the decision-making table will see the experts take up positions at the head of the table instead of merely being present at the table to aid and advise. This is why the pandemic accords are the latest waystations on the journey to an international administrative state that consolidates what Garrett Brown, David Bell, and Blagovesta Tacheva call the globe-spanning ‘new pandemic industry.’

The Trump administration, at least, is trying to resist the march to the collectivist destination. On 21 January, President Donald Trump signed an executive order to withdraw the US from the WHO. The WHO confronts a $2.5 billion shortfall between 2025 and 2027. Its financial situation is not helped by Trump’s decision to pull the US out. On 20 May, as the 78th meeting of the World Health Assembly got underway in Geneva to vote on the new pandemic treaty, Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F Kennedy, Jr explained why. Addressing his counterparts from other countries in a brief video message on X, he said the US withdrawal should serve as ‘a wake-up call’ to other countries that, ‘like many legacy institutions,’ the WHO has been corrupted by political and corporate interests and ‘is mired in bureaucratic bloat.’

Since inception, the WHO has accomplished important work, including the eradication of smallpox. More recently, however, its ‘priorities have increasingly reflected the biases and interests of corporate medicine.’ ‘Too often it has allowed political agendas, like pushing harmful gender ideology, to hijack its core mission.’ In an echo of my earlier lament above, Kennedy said that ‘The WHO has not even come to terms with its failures during Covid, let alone made significant reforms.’ Instead it has doubled down with the pandemic agreement ‘which will lock in all of the dysfunctions of the WHO pandemic response.’

‘Global cooperation on health is still critically important,’ but ‘not working very well under the WHO,’ Kennedy said. Countries like China have been allowed to exert a malign influence on WHO operations in pursuit of their own interests rather than in service of the people of the world. When it comes to democratic countries, actions of the WHO suggest a failure to acknowledge that its members are and must remain accountable to their citizens and neither to transnational nor to corporate interests. ‘We want to free international health cooperation from the straitjacket of political interference by corrupting influences of the pharmaceutical companies, of adversarial nations, and their NGO proxies.’

‘We need to reboot the whole system,’ he concluded, and shift our focus to the prevalence of chronic diseases that are sickening peoples and bankrupting health systems. This will better serve the needs of people instead of maximising industry profit. ‘Let’s create new institutions or revisit existing institutions that are lean, efficient, transparent, and accountable. Whether it’s an emergency outbreak of an infectious disease or the pervasive rot of chronic conditions,’ the US is ready to work with others.

That is a clear and compelling rationale put forward by Kennedy for the US withdrawal from the WHO. The international elite will circle the wagons to defend the expansion of the international administrative state. The political leaders in thrall to the expert class will genuflect to their advice. Those seduced by the idealism of international solidarity and others corrupted by the lucre of pharmaceutical lobbyists will not be persuaded by Kennedy. Competent leaders of self-confident countries, however, should take up his offer to nest the ethic of global health cooperation in a new specialised international organisation that better respects the health sovereignty of member states and the health needs of people.